Archaeology and chemistry: a new look at testimonies from the past

This article was originally published in L'Édition n°27.

Many archaeological and historical studies have been given a new lease of life thanks to advances in chemistry methods. At Université Paris-Saclay, researchers are developing different approaches for using their physics and chemistry skills to benefit archaeology.

A fragment of pottery, a deposit at the bottom of a bathtub, a piece of hardened textile... For chemists able to see their potential, these organic remains are real treasures and can reveal an individual's age, sex or diet, for example. So when these residues are found in an archaeological context, they take on a very special dimension, sometimes becoming the key to mysteries that archaeology alone cannot solve.

Philippe Charlier, doctor, paleopathologist and director of the Laboratory of Anthropology, Archaeology and Biology (Laab - Univ. Paris-Saclay/UVSQ) since 2018, is particularly fond of these types of residues. In his laboratory, where "disciplines are constantly interconnecting", the lecturer works in a completely interdisciplinary way, often combining medical and social anthropology in his research. He believes that the study of organic remains is an ideal entry point for blurring the boundaries between different specialities. "There is no such thing as 'soft' or 'hard' sciences; they are simply sciences," he says.

Paleoproteomics supporting history

Since 2023, Philippe Charlier and his team have been exploring an innovative technique called paleoproteomics. It uses proteomics, i.e. the analysis of all proteins, in an archaeological and paleopathological context. "The idea is to identify all the peptides, or pieces of protein, that make up a sample, so we can understand the nature of the sample and identify its constituent elements," explains the Laab Director. This technique has never been used before in archaeoanthropological research. Philippe Charlier has already solved many historical mysteries thanks to paleoproteomic analyses made possible by his collaboration with Jean Armengaud, Director of Research at the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA) in Marcoule. In 2023, the two scientists published two papers involving paleoproteomics. The first focused on Saint Leonard of Noblac, a religious figure who was a contemporary of Clovis and whose cause of death was still unknown. During an in-depth study of his relics, researchers found markers of a bacterial infection, mycetoma or "Madura foot", whose associated malformations would explain the Saint's death before his fortieth birthday.

The same year, another study, dedicated to the heart of Blessed Pauline Jaricot, a 19th-century French missionary figure, revealed no heart defects or traces of embalming to identify the cause of death or explain the relic's excellent preservation. "Paleoproteomics is making it possible to reopen historical files considered closed," says Philippe Charlier, who has also led several archaeological and anthropological missions for Laab, in Haiti, Cameroon and Benin. "This technique is particularly relevant when the DNA is too old or degraded and genetics is impossible. Proteins, on the other hand, always contain a wealth of information, particularly about the pathological state of individuals."

In 2024, as part of a research programme dedicated to Saint Helena, the island famous as the home of Napoleon I until his death in 1821, Philippe Charlier looked at artefacts that directly belonged to the emperor. Among them, the bathtub at his Longwood house, in which he spent a particularly lengthy amount of time after the development of his skin disease. The deposits accumulated in the metal joints of this bathtub had been in direct contact with the emperor and constituted a "particularly valuable" historical source for better understanding this infection, according to the lecturer.

Once the sample has been collected, purified and fragmented at high temperature, the individual peptides were analysed and compared with a database. Among the many elements found, the research team revealed the presence of botanical and mineral elements, as well as seawater and arsenic, often used in the 19th century as remedies for dermatological diseases. "These clues confirmed the use of seawater for therapeutic purposes at the time, probably in combination with other medicinal substances, either applied directly to the skin or in bath water," explains Philippe Charlier. Scientists also noted the presence of a pathogenic bacterium, Bacillus idriensis, potentially responsible for the emperor's skin infection or secondary infection. Conversely, none of the components found currently confirmed the widespread hypothesis that Napoleon suffered from scabies.

An enthusiast of famous patients, Philippe Charlier has also studied the remains of Jean-Paul Marat (2023) and Robespierre (2024). His next scientific publications, planned for June 2025, will focus on the embalmed heart of Voltaire and the skeleton of the painter Raphaël. "Another forthcoming scientific publication will be dedicated to Louis XIV, as the study of his heart has made it possible to identify the real causes of his death," he reveals.

Interpreting textiles

While human remains are an essential source of information for archaeology, other materials also preserve a wealth of usable data. Such is the case with mineralised textiles, the favourite object of study for Loïc Bertrand, researcher at the Supramolecular and Macromolecular Photophysics and Photochemistry laboratory (PPSM - Univ. Paris-Saclay/National Centre for Scientific Research, CNRS/ENS Paris-Saclay). "Mineralised textiles are organic materials whose shape is preserved over time by contact with a metallic object, particularly copper- or iron-based, and the presence of water," explains the scientist. "Some are almost completely transformed into mineral form, but others still include a large organic fraction." Archaeologists are finding these remains in rich Iron Age burials, in which it was customary to place metal objects wrapped in cloth.

Loïc Bertrand and his team are now trying to better understand the mechanisms behind this phenomenon. "It is interesting to note that mineralisation involves several types of cloth. From a chemical point of view, textiles based on keratin (wool) and cellulose (cotton, linen, hemp, etc.) are very different. So there are several physical and chemical mechanisms that lead to this long-term preservation." Apart from these processes, organic fabrics usually degrade very quickly in temperate environments, causing wool, cotton and silk to disappear within a few years. "Without being able to make an estimate, the fraction of fabrics we find in an archaeological context is certainly infinitesimal," confirms Loïc Bertrand, aware of the "rare and exceptional" aspect of his object of study.

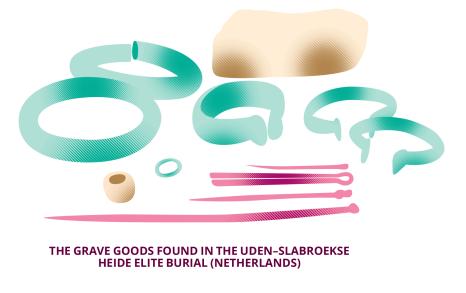

In 2024, Loïc Bertrand and his team published a scientific paper on fragments of mineralised textiles from a rich burial site at Uden-Slabroekse Heide (Netherlands), estimated to date from the 8th century BC. The fragments, preserved in contact with the bronze and iron ornaments of the deceased, were analysed using synchrotron X-ray microtomography, a non-invasive technique akin to medical scanning, which reconstructs a 3D volume of the object from X-rays. The results suggested that the fragment belonged to a woollen dress with a "houndstooth" pattern, making it the oldest garment everfound in the Netherlands. Complementary work by Dutch and Italian scientists also revealed the presence of red and blue dyes on the dress, the oldest evidence of cochineal being used as a dye in the Netherlands, before it was imported from South America.

For Loïc Bertrand, the Uden-Slabroekse Heide site is a particularly relevant field of research. In addition to its major importance in the country's history, the site's interest also lies in the quality of its excavations. "The study of the archaeological material on this site is extremely detailed and expertly conducted. The archaeologists removed an entire block of sediment, which was then studied and dissected directly in the laboratory. This excavation technique documents the different layers more accurately, avoids contamination from the terrain and better preserves the organic textile material present, particularly traces of dyes."

While the Netherlands and more and more other modern excavation sites are taking into account the need to preserve and document these minute material witnesses, Loïc Bertrand laments the low regard in which archaeologists held textile materials until the mid-20th century. "On the sites, scientists were using an erroneous hierarchy of objects, where finding metal was more important than finding ceramics or glass. This was followed by 'less noble' organic materials such as leather, wood and fabric." The researcher also believes that the "feminine" connotation of textile practices played a role in the prolonged maintenance of this hierarchy. Thus, in most burials excavated before the advent of chemistry, textile remains - difficult to display to the public and to study with existing techniques - were systematically eliminated to better show the weapons, jewellery and other metals they covered.

Today, thanks to advances in chemistry, scientists have a better grasp of the importance of these objects, particularly in understanding different uses, the dynamics of species domestication, production and exchanges between populations. Loïc Bertrand is particularly interested in the changes in perception of these material witnesses, for their historical perspective. In 2024, he published a scientific article on the history of textile discoveries from the 16th to the 20th century. "It is very interesting to study past descriptions and the evolution of knowledge. It allows us to take a different look at current practices. Something that will seem obvious in a few decades may not even be understood today."

The researcher enjoys testing different working methodologies and combining disciplines in an attempt to identify future research breakthroughs. His latest contribution, published in 2025, tested for the first time a technique based on luminescence decay, i.e. the emission of light, with the aim of better understanding the fossilisation conditions and paleoenvironment of a fossil shrimp.

Combining carbon-14 and organic geochemistry

Like Loïc Bertrand, Emmanuelle Casanova, a researcher at the Laboratory for Climate and Environmental Sciences (LSCE - Univ. Paris-Saclay/UVSQ/CNRS/CEA), also became known for the development of new innovative methods. The chemist, who is also scientific manager of the organic geochemistry platform and deputy team leader of the GeoTrac team, is behind a special carbon-14 dating technique that uses lipids, coupled with organic geochemical analyses. "Lipids from dietary fat residues are invisible to the naked eye and are particularly well-preserved sources of carbon in archaeological ceramics," she explains.

For this so-called "molecular" technique, Emmanuelle Casanova isolates specific molecules for precise dating. Depending on the quantity of lipids preserved, they are either transformed into graphite or simply burnt and transformed into carbon dioxide (CO2), before finally being dated thanksto their carbon-14 content. "Radiocarbondating on specific molecules is a rare technique, particularly for archaeological studies," adds the researcher. Thanks to this new experimental method, Emmanuelle Casanova works with research teams all over the world. Between 2021 and 2023, she worked more specifically on Southwest Asia as part of the MSCA VARGAH project, aimed at documenting the development of mobile pastoralism in Iran during the Neolithic period. The dating technique developed by the researcher is particularly useful here, as the region's arid climate does little to preserve the collagen in the bones required for conventional radiocarbonanalysis.

In addition to the absolute dating of ceramics based on the food remains they contain, Emmanuelle Casanova uses methods capable of determining the source - animal or vegetable - of these residues.This precision is made possible by identifying the molecules present and their isotopic signature, i.e. their carbon-13 content. Thanks to her research, the scientist has been able to identify and date, for example, the introduction of cattle and goat milk processing in Central Europe by the Linearbandkeramik cultural group, 5,400 years BC. "It is particularly interesting to identify the presence of dairy products, as they imply the use of milk and therefore the presence of domesticated animals. This organic chemistry data therefore adds to our knowledge of the region's pastoral communities and provides information on the population sedentarisation process." In 2022, the researcher also worked on Central Asia, dating the use of equine products at the prehistoric sites of Bestamak and Botai (Kazakhstan), with the latter presenting the oldest evidence of equine domestication. Lipid residues from equine products taken from pottery were dated to the 6th and 4th millennia BC respectively.

Two years later, Emmanuelle Casanova published an analysis of three Iron Age funerary ceramics from the Sialk necropolis in Iran, now in the Louvre Museum. Her aim was to determine the function of this particular pottery, found only in funerary contexts in this region. A study of the organic residues present in the spout of one of the pots indicated the presence of dairy fat, probably in a liquid state, given the shape of the pot. Samples from another pot suggested the presence of ruminant carcass fat, also in a liquid state, which could have come from blood or heated fat, for example. "Analysis confirms that these objects were used to pour products of various kinds. Given the archaeological context and the specific typology of the ceramics, they were potentially used for funerary libation rituals," in other words liquid offerings, summarises the researcher, who is careful not to over-interpret her results.

While it is currently impossible to identify the nature of the dairy products in an archaeological context due to the lack of specificity of the molecules found, Emmanuelle Casanova believes that technical developments in the field of chemistry, particularly innovations linked to the detection limits of the instruments, have the potential to resolve these questions within a few years. Pending these new advances, the researcher is currently leading the AGROCHRONO project, winner of an ERC Starting Grant in 2024. Following on from VARGAH, this project looks at the routes along which agropastoralism spread between Iran and Pakistan during the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods. The work of Emmanuelle Casanova and her team should eventually lead to dissemination models aimed at better understanding the arrival and development of agropastoralism in this region.

The importance of "frontier" projects

Doctors, anthropologists and chemists, Loïc Bertrand, Philippe Charlier and Emmanuelle Casanova share a passion for interdisciplinarity in their research. In addition to their direct application to history and archaeology, the physical and chemical techniques these scientists have developed over the years can also be used in much broader fields. Philippe Charlier explains: "All the protocols we publish can be used in the very short term in forensic medicine or forensic anthropology, for example to better study the traces left at the scene of a crime or the discovery of a corpse. Instead of working on guinea pigs, our development tests are carried out on the remains of saints or kings of France!"

For Emmanuelle Casanova, it is "the combination of the expertise of the people involved" that makes each research project unique and "provides a more global vision and a better level of knowledge than classical archaeology". Loïc Bertrand, for his part, praises the richness of the archaeology and chemistry community at Université Paris-Saclay, and enjoys working on "frontier objects" that "can be approached from different disciplinary perspectives," enriching it thanks to "colleagues with very diverse backgrounds".

References :

- Philippe Charlier, Jean Armengaud, et al. Can Napoleon's skin disease and treatment be identified from paleoproteomic analyses of his last bathtub (1821)?, Journal of the European academy of dermatology and venereology, 2024.

- Clémence Iacconi, Loïc Bertrand, et al. The oldest dress of the Netherlands? Recovering a now-vanished, colour pattern from an early iron age fabric in an elite burial. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2025.

- Emmanuelle Casanova, et al. Unveiling the function of long-spouted ceramics at Sialk, Iran: Insights from organic residue analysis. Archaeological Research in Asia, 2024.

This article was originally published in L'Édition n°27.

Find out more about the journal in digital version here and on Calameo.

For more articles and topics, subscribe to L'Édition and receive future issues: