Solar winds and magnetic clouds: how can we study and predict space weather?

Far from being calm and empty, the interplanetary environment is in fact a place of sometimes violent storms carrying clouds and winds, all originating from the Sun. It is precisely to study the surface and activity of this gigantic ball of molten plasma that satellites like Solar Orbiter leave Earth for space. Using the data collected, astrophysicists run simulations to predict the weather in space and help control its impact on Earth. (This article was originally published in L'Édition n°28.)

Is it possible to propel a spaceship with a sail, as in Star Trek? While the technology remains science fiction, the wind that would drive it is very real. Indeed, the interplanetary environment is not as peaceful as is usually assumed. It is swept by winds, crossed by clouds and sometimes disturbed by storms. However, these space-weather phenomena are not the same as those observed in Earth's atmosphere. This is because they have a different origin, they emanate from the Sun.

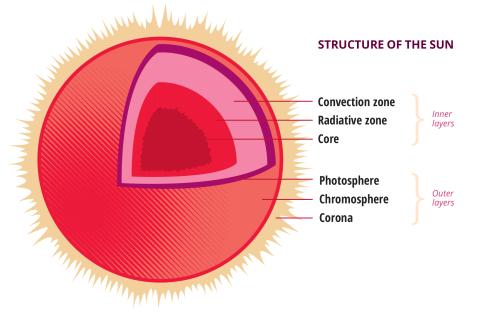

The Sun is an immense ball of plasma - the fourth state of matter - with a diameter of around 1.4 million kilometres, or 110 times that of Earth. At its centre, nuclearfusion reactions take place, transforming hydrogen atoms into helium atoms. These reactions are said to be exothermic: they generate heat. This heat is transported outward from the star’s interior by radiation and then by convection, until it reaches the solar atmosphere and its various layers. The photosphere, about 500 km thick, is the Sun's surface layer of the Sun: it emits light and constitutes the visible surface. Beyond it lies the chromosphere, the middle layer of the atmosphere, around 1,000 km thick and visible in red during total eclipses. Finally, there is the corona, the outermost layer, which is much thicker and extends for nearly 10 million kilometres. It is within this solar atmosphere that winds, storms and eruptions occur.

A magnetic field generated by the dynamo effect

The Sun, like a colossal magnet, also has its own large-scale magnetic field, similar to that of Earth. This is generated by what is known as the dynamo effect. "It is exactly like a bicycle dynamo," explains Barbara Perri, a researcher at the Dynamics of Stars, Exoplanets and their Environment Laboratory (LDE3) within the Department of Astrophysics (DAp - Univ. Paris-Saclay/French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission, CEA). "Pedalling causes a small magnet to move inside a coil, transforming kinetic energy into electromagnetic energy." The resulting electric current powers the bicycle's lights. The Sun, which is not solid, behaves differently: the differential rotation between the equator and the poles, and the resulting shear, generate the kinetic motion that underlies the electric currents and magnetic fields.

However, the Sun's magnetic field has an unusual feature: it reverses periodically, every 11 years. "We've been observing this reversal for at least four hundred years, and it remains remarkably regular," notes the astrophysicist. This solar cycle is marked by changes in the Sun's activity, with its peaks historically identified by variations in the number of sunspots on the star's surface.

To understand what these sunspots are, we need to look at the local magnetic fields. In addition to its global magnetic field, the Sun is also the site of smaller-scale magnetic activity. These local disturbances disrupt the convective motions in the photosphere, at the star's surface. "The local magnetic field prevents convection from being as efficient as elsewhere, leaving the zone colder, denser and therefore darker," explains Éric Buchlin, a researcher at the Institute of Space Astrophysics (IAS - Univ. Paris-Saclay/French National Centre for Scientific Research, CNRS).

As local magnetic fields are more intense during the Sun's maximum activity, more sunspots can be seen on its surface. These local phenomena are also responsible for coronal heating. For while the Sun's surface (photosphere) has a temperature of about 5,800 kelvins (approx. 5,500°C), the temperature in the corona rises to a million kelvins (K). This difference is due to the thermal energy released by local magnetic loops, which also carry matter from the chromosphere. This generates filaments or flares in the solar atmosphere.

Solar Orbiter, a mission to observe the Sun

Scientists use powerful telescopes to observe the Sun’s activity from Earth. But many factors, such as the Earth's rotation and its atmosphere, interfere with the fine details of these observations. They therefore need to send satellites into space, to get closer to the star. Such is the case of the European Space Agency's (ESA) Solar Orbiter mission which launched in February 2020. A veritable flying laboratory, this observation satellite carries ten scientific instruments designed to study the Sun up close. Two of these, EUI (Extreme Ultraviolet Imager) and SPICE (Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment), were partly designed and are now operated by IAS researchers.

EUI is a telescope capable of producing high-resolution images of the solar disk and atmosphere. Over more than four hours, the device takes an image of the Sun made up of a mosaic of twenty-five images with a total of 83 million pixels and at a resolution ten times greater than a conventional 4K screen. It is the result of a European collaboration led by the Royal Observatory of Belgium and involving the IAS and the Institut d'Optique Graduate School in the design of its mirrors. It can operate in the extreme ultraviolet, revealing the outer layers of the atmosphere. Therefore, it takes full advantage of the temperature differences between the various layers.

The "cooler" photosphere emits mainly radiation in the visible range. The much hotter chromosphere and corona emit radiation mostly in the ultraviolet. In images taken in visible light, these layers appear far less bright, as they are drowned out by the photosphere and are virtually invisible. But everything changes in the extreme ultraviolet. "For instance, loops are clearly visible there as they correspond to very hot regions (up to several million kelvins)," explains Éric Buchlin. As a result, the images of the outer layers produced by EUI are of remarkable precision.

Alongside the EUI on Solar Orbiter, the SPICE instrument also operates in the extreme ultraviolet. This is an imaging spectrometer, capable of observing the Sun

at specific wavelengths and producing spectroheliograms, i.e. monochromatic images of the Sun taken at these wavelengths. By capturing the radiation emitted

by different atoms, this instrument can be used to distinguish between hydrogen, carbon, oxygen and neon emissions. In this way, SPICE has provided the first complete image of the Sun in the so-called Lyman beta line, one of the characteristic lines in the hydrogen emission spectrum.

These images aim to gain a better understanding of the plasma's dynamics in the layers of the star's atmosphere, i.e. to determine its temperature, density,

velocity and composition and consequently, reveal what is happening. In addition to EUI and SPICE, Université Paris-Saclay is involved in four other instruments on the Solar Orbiter satellite: PHI (Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager), STIX (X-ray Spectrometer/Telescope), RPW (Radio and Plasma Wave Analyser) and SWA (Solar Wind Analyser).

Unprecedented images of the Sun's poles

In addition to the quality of its instruments, Solar Orbiter is following a very specific trajectory. Unlike the other satellites already orbiting the star, Solar Orbiter is not positioned on the ecliptic, the great circle on the celestial sphere that traces the Sun's annual path as seen from Earth. Its orbit is currently inclined at 17° to this plane and this inclination should increase during the mission: "Solar Orbiter will have an increasing inclination, reaching 30° at the end of the mission, when we'll finally be able to see the solar poles," confirms Éric Buchlin.

This is the added value of the satellite's trajectory. It provides a better view of the star's north and south poles, which are nearly impossible to observe from Earth or using other satellites. This is how Solar Orbiter provided the first images of the solar south pole last June. The SPICE instrument then precisely tracked the spectral lines of the different atoms present in the Sun and measured how fast the plasma masses move within its layers. The study of these plasma movements, which are the source of solar winds, is proving very interesting, as it provides information on space weather and, in particular, the acceleration of solar winds.

Observing the Sun's poles is also of great importance, as they are the source of its magnetic dipole. Collecting more data about them opens the way to a deeper

understanding of the solar magnetic field. "There's a huge potential for exploration," confirms Éric Buchlin. "This is where the main magnetic field originates and we'll

actually be able to measure it for the first time." The study will also improve our knowledge of the 11-year solar cycle. At the end of this cycle, the north and south poles reverse and the Sun moves from a quiet to an active, eruptive state, and vice versa.

Winds and clouds in the solar system

By observing the Sun's surface, however, scientists can go further, gaining insights into the winds and clouds that move through interplanetary space. The solar

wind is a hot plasma, composed mainly of atoms of hydrogen, electrons and protons - electrically charged particles. "These particles are accelerated by the injection of energy produced by coronal heating. So there's a stream of particles flowing from the Sun into the interplanetary environment at considerable speeds," explains Barbara Perri.

A distinction is drawn between slow solar wind, which reaches Earth at 400 km per second, and fast solar wind, which travels at 800 km per second. By way of

comparison, the fastest wind ever recorded on Earth reached a speed of around 0.1 km per second. Solar wind speeds are directly related to the magnetic field lines on the Sun's surface. "When the solar magnetic field is said to be open, so when it extends outwards from the Sun, particles are accelerated and produce fast solar wind. Conversely, if the wind encounters a so-called closed magnetic field, which is one that loops back on itself, the particles are slowed and slow solar wind is observed."

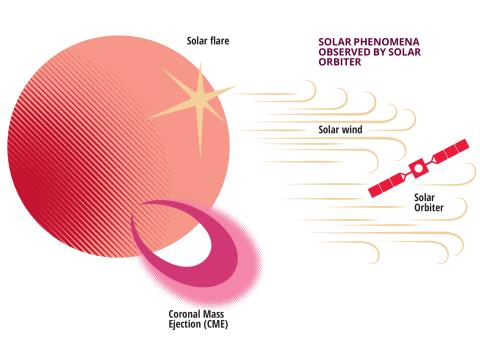

Although its intensity and direction vary, the solar wind is always present in the solar system, as a kind of background noise. In addition to this continuous stream, there are impulsive events that occur suddenly and unpredictably, such as solar flares; large bursts of light on the Sun's surface. "This is a large release of magnetic energy in the form of light, which will accelerate everything around it," describes Barbara Perri. These solar flares are sometimes accompanied by a release of material trapped in the solar magnetic field. This is known as a coronal mass ejection (or CME). "Strictly speaking, we should call it a "coronal ejection of mass", because although the ejection takes place in the corona, the material itself originates mainly from the lower layers," notes Éric Buchlin.

This material, ejected into the interplanetary medium, forms magnetic clouds. Small at first when they are close to the Sun, these clouds expand and grow in size as they advance into the interplanetary space, carried by the solar wind. They grow to between ten and hundred times the size of Earth, and may even reach it, depending on the strength, direction and disturbances of the solar wind.

Modelling interplanetary winds to forecast space weather

This is why scientists are endeavouring to model space weather. They hope to predict when events like CMEs risk reaching our blue planet. "The solar wind is

the main vector connecting the Sun and the Earth. Every meteorological event produced by the star is carried by this wind," points out Barbara Perri. However, it is not possible to predict all events with the same reliability. During a solar flare, the burst of light and associated particles travel at the speed close to that of light, reaching the Earth in eight minutes, making them very difficult to predict. Slower CMEs take between one and five days to reach Earth, which makes the prediction horizon easier and allows them to be anticipated. "As soon as we see something on the Sun's surface, we run simulations!" says the scientist.

Barbara Perri and her team have worked on the interaction between wind and clouds to understand how clouds propagate, and in particular how the solar cycle influences this propagation. "We took exactly the same CME and tested it against solar wind conditions corresponding to minimum and maximum solar activity." Based on these predictions, the researchers have shown that although there are more solar flares during peak solar activity, this does not coincide with the events that have the greatest impact on Earth.

The explanation lies in the effect of the solar wind. During solar activity minima, solar wind is highly structured and plays a key role in determining plasma cloud

direction and propagation. An intense event occurring far from the solar activity peak is therefore more easily transported to Earth. However, during peak solar activity, the background noise is extremely chaotic, and the plasma cloud may be deflected or redirected, never reaching Earth. This highlights the importance of understanding and characterising the solar wind, as it can have a considerable impact on estimates. Accurate and reliable observations of the solar surface guarantee the quality of the predictions.

That's where satellites like Solar Orbiter come into play. "With this new satellite, we can once again observe the far side of the Sun for the first time in years. For six months of the year, it gives us information that we can't access from Earth," explains Barbara Perri. In the images transmitted by the satellite, scientists noticed structures that appear and then disappear. The LDE3 team compared the structure of the solar wind using models that either included or excluded these new data. The results obtained by the two simulations have notable differences, demonstrating the importance of observing the far side of the Sun to achieve the most reliable models possible.

Barbara Perri and her team are now involved in a new project, WindTRUST, which aims to improve the accuracy of their simulations further. In this context, these scientists are developing models that can evolve over time and take into account the very rapid changes observed on the solar surface. The team is also working on model evaluation: "We're developing a set of automatic tools to quantify very precisely how much we can trust a solar wind forecast," adds the astrophysicist.

Space weather: real impacts on Earth

It is important to study the solar winds and plasma clouds that sweep through the solar system and their chances of reaching the Earth, because their effects on the planet are tangible and visible, especially on human infrastructures and people. "There are three levels of impact: in space, in the atmosphere and on the ground," explains Barbara Perri. In space, magnetic clouds are not only a danger to astronauts during spacewalks, but also to satellites, whose solar panels can be severely damaged.

At the atmospheric level, solar flares generate electrical currents capable of disrupting communications passing through the atmosphere, leading to radio blackouts and GPS disruptions. "Finally, if the currents in the atmosphere become too strong, they can trigger effects on the ground. Electric

currents form in power installations, pipelines and electricity grids. These are called ground induced currents, or GICs," adds the scientist. If they affect the

electricity grid, these currents can cause power cuts. That's what happened in 1989, when the most violent space weather event in modern times damaged a power plant in Quebec, cutting off water and electricity for three days.

In the face of such impacts, astrophysicists provide the data they collect, and their simulation models, to monitor space weather. This is the role of the Multi Experiment Data and Operation Center (MEDOC) platform, involving Université Paris-Saclay, the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) and the

French Space Agency (Centre National d'Études Spatiales, CNES). This data and operations centre centralises the observations collected by space missions such as SOHO - a solar satellite launched in 1995 - and Solar Orbiter. In addition to this raw data, MEDOC provides derived maps, models, simulation results and explains how these are interpreted. Université Paris-Saclay is also involved in ESA's Space Weather project. This aims to develop a platform containing publiclyavailable

tools (currently in a pre-operational phase) for tracking space weather forecasts. When will we have a weather forecast for the stars?

References :

- Perri et al., Impact of far-side structures observed by Solar Orbiter on coronal and heliospheric wind simulations, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 2024.

- Perri et al., Impact of the Solar Activity on the Propagation of ICMEs: Simulation of Hydro, Magnetic and Median ICMEs at the Minimum and Maximum of Activity, The Astrophysical Journal, 2023.

- Brooks et al., Plasma Composition Measurements in an Active Region from Solar Orbiter/SPICE and Hinode/EIS, The Astrophysical Journal, 2022.

- Bernoux et al., Forecasting the Geomagnetic Activity Several Days in Advance Using Neural Networks Driven by Solar EUV Imaging, Journal of Geophysical Research:Space Physics, 2022.

This article was originally published in L'Édition n°28.

Find out more about the journal in digital version here.

For more articles and topics, subscribe to L'Édition and receive future issues: